When it is hot, you might need to balance the need to be outside with the danger and discomfort of heat. Sometimes, parks are no exception to it: either they don’t have enough shadow and cooling spots, or these shadows cannot be comfortably used.

That’s why, to maximise the cooling potential of six parks and create new cooling solutions during heatwaves, the EUI Time2Adapt project has experimented with temporary urban furniture. What’s new about it? That’s what we’re going to see!

1. A user-generated solution

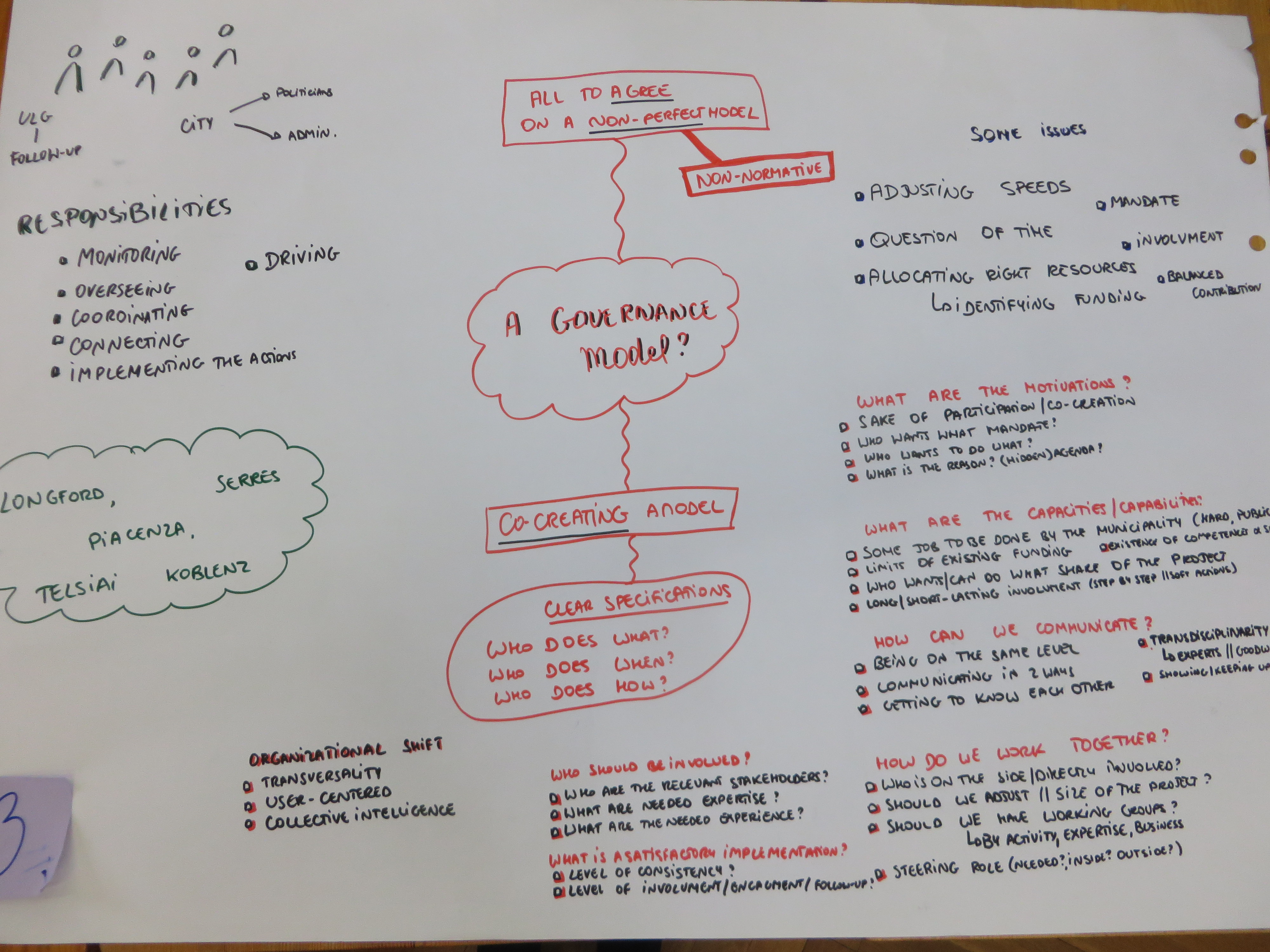

First and foremost, for five out of the six parks, actual and potential users of the areas geared the process. SEED NGO reached out to them via a cargo bike parked at community events (such as a music school’s opening). Through a series of workshops, they also:

- Concerted with residents to identify the way they use or not the park, and what they would like to see happen there;

- Co-designed the urban furniture based on their initial spatialisation and first shapes; and,

- Co-constructed the furniture, after political approval of the sketches.

Experience showed that the cargo bikes worked when users were already present and had time to give their opinion, for example during an existing event, or during a Sunday morning market rather than a Saturday morning one. Workshops were better organised when they took place with local NGOs acting as intermediaries (such as a social centre or a youth prevention club). Being as concrete as possible enabled the participants to project themselves and to own the project.

Co-construction of the furniture at Park of Maison Folie Moulins, spring 2024 © SEED

2. Frame your action well!

After the first experimentation in the park of Maison Folie Moulins in spring 2024, the project acknowledged it was crucial to work upstream with municipalities to validate the technical specifications and political guidelines. For example, electrical networks could limit the installation on a given spot, some places could be prone to antisocial behaviour leading to the need to keep side laneways visible for patrolling services, local projects might already be planned (renovation or participatory budget projects), or, political representatives also have their own priorities and visions that must be taken into account from the outset.

Based on these and on joint meetings, SEED committed itself to co-produce the urban furniture within an agreed frame with restricted contestation possibilities for the municipalities: this approach helped manage residents’ expectations — avoiding situations where community proposals might later be rejected due to missing technical or contextual information.

3. So, eventually, what can you find in these parks?

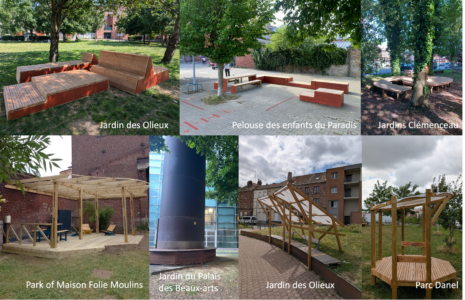

First of all, new urban furniture was built in places where cooling spaces already existed. The use of shadows provided by trees was maximised with the installation of benches and laying areas in Jardin des Olieux, a meeting space with benches and tables at the Pelouse des enfants du Paradis, a pergola and seats at the Park of Maison Folie Moulins, and a circular bench in Jardin du Palais des Beaux-arts, all in Lille. A “snail bench” was also built in Jardins Clémenceau in Loos.

In terms of new furniture in places with no cooling spaces, resting areas with shade sails were created : benches in Jardin des Olieux in Lille and kiosks in Parc Danel in Loos.

Time2Adapt’s experimental urban furniture, summer 2024 and 2025 © Time2Adapt

4. How can you know it exists?

Now, a main issue is to put these spaces in residents’ mental map for when the weather is too hot indoors, as the neighbourhoods targeted by the project suffer from small and poorly isolated dwellings. Beyond the furniture which is visible thanks to its location on passing areas, the project has also worked on the signposting, to make the other spaces more visible: an invitation to enter was for example posted on the walls of Jardins Clémenceau or on the way to the Arsenal Park – in which no furniture was experimented. It was already noted, though, that some furniture like the kiosks of Parc Danel, might need more promotion as they are hidden from the main paths.

Signposting towards Jardins Clémenceau and Arsenal Park © François Lescaux and © Ophélie Tainguy

5. Now that they know this, will residents change their habits?

Residents and visitors love using these new spaces. Evaluation is still ongoing, but at this stage every time the project team passes by this new furniture, it is occupied.

On the one hand, some of the furniture is intact – showing the respect and appreciation of the residents. On the other, there have been some deteriorations (wild barbeques, broken curtains): to a certain extent, this means they are used as well. On the contrary, some users of the snail bench have complained about some pigeon’s manure which needed to be cleaned: it shows its success!

As for the new shadows created by the sails in Jardin des Olieux, residents wish they had been more of them!

Last but not least, people have been impressed to see the pace at which their inputs were taken into account, and the fact that the furniture was being installed within weeks and not within months to which they used.

6. It’s only the beginning!

The furniture installed within Time2Adapt is temporary and experimental: it will last as long as it is intact and/or until further plans are being developed. This experimentation is meant to support municipalities in redesigning their cool areas with a long-term prospect. For example, renovation is already planned at the Pelouse des enfants du Paradis : the furniture might be redirected to another green space which is part of the Time2Adapt’s experimentations, the Jardin de la Pouponnière. A participatory budget project will also be implemented in Jardin des Olieux: collaboration with local NGOs and community organisations could also lead to other experimentations.

The methodology for these experimentations, the learnings as well as practical support will be provided to the municipalities joining the Call for Project in Phase 2 of Time2Adapt. This will help building a toolbox useful for all the municipalities to replicate the experimentations.

Stay tuned for the Call for projects if you’d like to experiment this as well!

Building the snail bench at Jardin Clémenceau, Spring 2025 © Ophélie Tainguy

Reposted from Portico