The case of Integrated Actions Plans of the URBACT MAPs network, output from the Transnational Meeting of 12-13 December 2017 in Szombathely, Hungary.

WHERE DID WE START FROM?

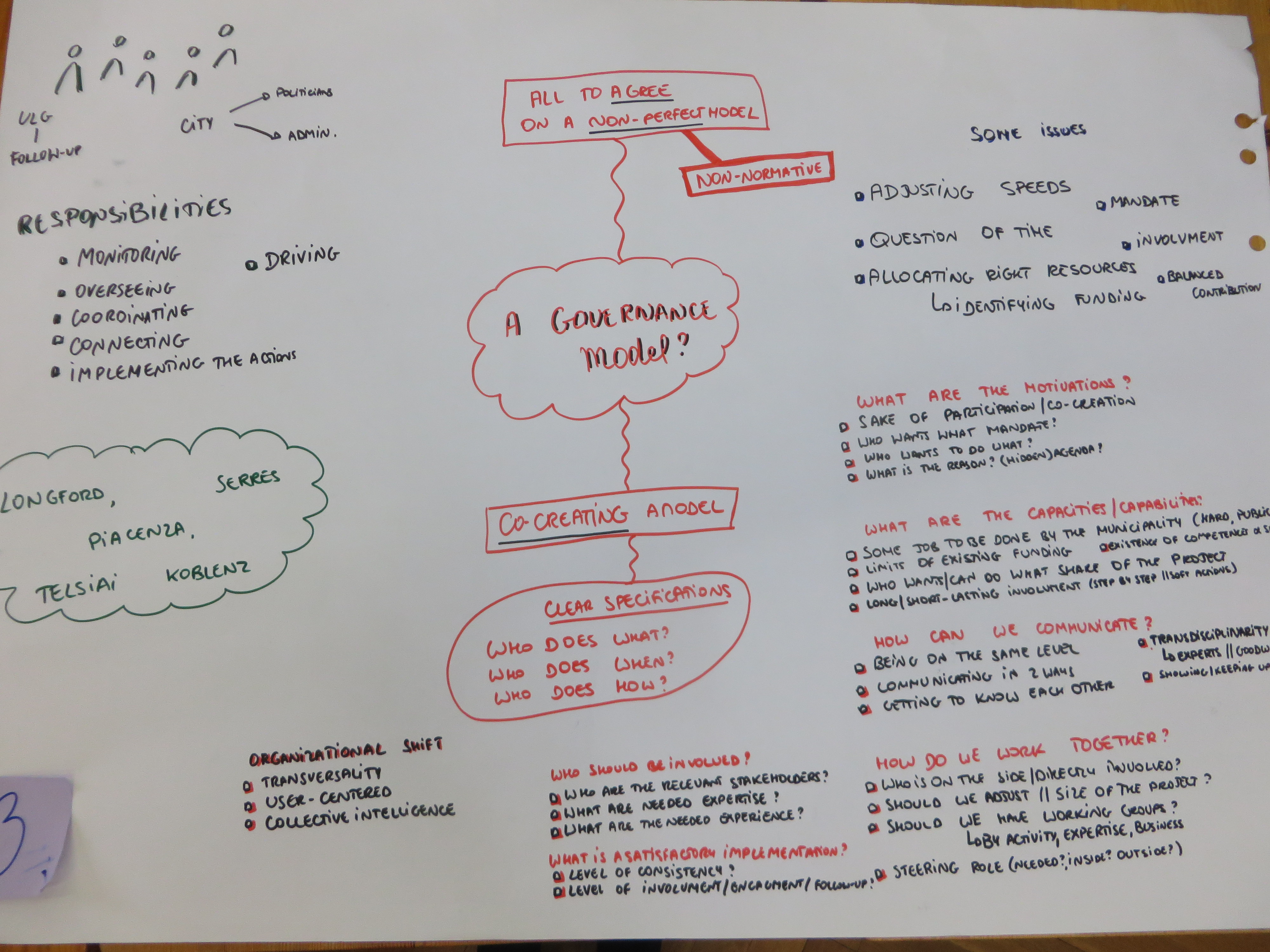

The cities of the MAPs network who took part in the meeting in Szombathely were quite stressed about the design of the governance model to ensure an adequate implementation of their Integrated Action Plans (IAP)[1]. How can we ensure that everybody will take part in it? How can we ensure that responsibilities are well allocated? The City administration should let go! (vs. the City administration should be in strong control of the process) We are engaging the ULG members but they do not want to co-create, merely to react on proposals! We want to be sure that our governance model is relevant and effective!

These were some of the questions and remarks by the participating partners. They felt quite pressured about the “perfect” model they should attain and that would be meet the needs of the IAP but also a societal move towards greater co-creation of local policies.

What the discussions of the groups made clear was that there is no single governance model that would fit all. Each local cultural and political context is different. The status of the areas where the actions will take place is varying and not always clearly defined. Some IAP still rely on a range of possible scenarios. How, in this case, can cities identify the relations and responsibilities that should be shared between relevant stakeholders?

SOME ISSUES COMMONLY FACED BY CITIES

Working together on the urban (re)development of an area is not an easy task. The pace of the stakeholders involved (notably City administration and ULG members) is not the same: from directly acting on the ground to long procedural steps. This is without mentioning the timeframe that political mandate brings in. Similarly, the question of availability is clearly a strong concern: those professionally involved have potentially more (paid) time to dedicate to the project than (unpaid) volunteers. At the same time, the involvement of professionals is limited by the remits of their positions and time planned for the project, whereas volunteers have a greater (potential) flexibility in their involvement. Finally, professionals are limited by cooperate rules, whereas volunteers have (conceptually at least) unlimited freedom.

In relation to those, the question of mandate is crucial: who should be doing what and for what reason? Who will be responsible and accountable to the others? As such, how can the proposed governance model ensure that there is an adequate involvement of each participant with a balanced contribution?

Finally, how can administrations allocate suitable resources for the work to be carried out? How can financial and human resources be adjusted for the good functioning of the model?

PEOPLE AND RESPONSIBILITIES

For the participating partners, there are three main groups of actors: stakeholders – members of the so-called URBACT Local Group members (NGOs, public stakeholders, private stakeholders, …); and inside the Municipalities: the administration and the elected representatives. Monitoring, overseeing, coordinating; Connecting; Mediating, negotiating; Deciding; Driving; Advising; Building capacity; Translating; Implementing the actions; Formalising; Managing the funding: these are a series of roles and responsibilities to be included in the governance model that the partners identified.

CO-CREATING A GOVERNANCE MODEL

Yet, cities are strongly bound by a normative pressure and the way to ensure they have a “good” governance model. However, how can cities ensure that the model will work if it has been designed in silo in the administration, and then submitted to the ULG members and other stakeholders for – if not consultation – validation?

As such, it is important for cities to co-create a model, together with those (potentially) involved in the governance of the IAP, by asking themselves a series of questions and identifying the points of (dis)agreement on who should do what and when. Such an activity that can be organized, for example, as a (series of) workshop would ensure that everybody is accepted for his/her available contribution, respected for it, that everybody supports the proposed governance model and that implementation becomes smooth, with adequate – direct and transparent – communication channels.

Below are a series of questions that can steer the discussions and enable co-create a model that fits everybody the best.

[tx_row]

[tx_column size=”1/2″]

Who should be involved?

- Who are the relevant stakeholders? (Have they been clearly mapped or should be mapped again, are the same as during the URBACT network?)

- What are the needed expertise? (practitioners’, academics’, citizens’, companies’, NGOS’, …)

- What are the needed experiences? (on the site, outside the site, in the administration, …)

- …

What are the motivations of those involved in the governance?

- Is participation and co-creation an end in itself?

- Should participation be “forced”?

- Who wants to do what?

- Who wants what mandate?

- What is the reason for participants’ involvement?

- What is the (hidden) agenda of each of the participants?

- …

What are the capacities and capabilities of each of the participants?

- What works can be done only by the municipality? (hard work, public works)

- What are the possibilities and limits of the current human and financial resources?

- Who wants and can do what share of the project?

- What should be the involvement of participants (long-term, short-term)?

- …

[/tx_column]

[tx_column size=”1/2″]

How can the participants communicate?

- How can we ensure everybody is at the same level?

- How can communication be made in two (or more) directions?

- How can participants can get to know each other?

- How to work in a transdisciplinary way?

- How to keep the momentum?

- …

How can participants work together?

- Who is on the side/directly involved?

- Should the participants adjust the way they collaborate depending on the size of the individual projects?

- Should the participants set-up working groups? (by activity, expertise, business)

- Should there be a steering role? (if so, inside, outside the administration?)

- Should those not paid be compensated for their participation?

- What commitments should be made from the individuals to the institutions?

What is a satisfactory implementation of the IAP?

- What should be a level of consistency?

- What should be the level involvement / engagement and follow-up of the participants?

[/tx_column]

[/tx_row]

THE NEED FOR A PARADIGMATIC CHANGE TO OCCUR

On the paper, such a model is promising and municipalities as well as stakeholders should adopt it. Still, such a process keeps on requiring a paradigmatic change in the way we design cities. In conclusion, it will be important for all those involved to bear in mind some concrete steps that should take place:

- Developing a user–centered approach, borne by all those involved in the governance model, based on goodwill and acceptance of what everybody can and should do;

- Such a an approach can be supported methodologically by collective intelligence and co-creation design, whereby specific tools enable each to participate at their own level;

- This requires also public administrations as well as other involved organisations to develop transversality and work across silos;

- This would in turn lead to a deep and incremental organisational shift.

[1] An URBACT Integrated Action Plan analyses problems and opportunities, addresses specific needs by defining expected results, and prepares a set of actions in co-production with stakeholders. More about in the URBACT toolki and URBACT II Local Support Group Toolkit (2013) and the USU 2016 participants learning kit.