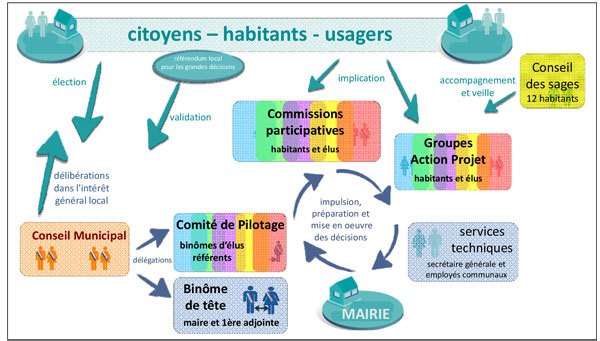

In 2014, a group of citizens of Saillans – 1 200 inhabitants in Drôme, France – concerned about acting directly for their city, and in the light of increased well-being, presented themselves, apolitically, for the mayorship of the city. They won the elections and paved the way for a new type of city governance. They particularly sought to address two main caveats in the traditional way city councils and city governance in general work: on the one hand the Mayor and the deputy mayors’ appropriation of all the city power; on the other, the low participants of inhabitants, merely asked to express themselves through elections once every 6 years.

The city governance focuses on three main pillars:

[tx_row]

[tx_column size=”1/3″]

1. Collegiality, in order to give back a concrete content to citizenship, with :

- 7 Thematic Participatory Commissions, coordinated by two elected people, gathering all the citizens (20-60 people) who wish to have a global reflexion, to design visions and to prioritise of concrete actions to be set up;

- Action-Projects groups, composed of at least an elected person and a minimum of 6 citizens which prepare, follow-up and implement a concrete action that was defined by a Commission.

230 people, i.e. 24% of the adult population take part in the Commissions and AP Groups. The decision to launch and finance an action remains validated by elected representatives in a Steering Committee.

[/tx_column]

[tx_column size=”1/3″]

2. Participation, at the heart of the process through :

- Information and transparency: the Steering Committee is open to the general public, a Q&A session is organised at the end of each City Council, all meetings are reported through minutes which are available on line, public meetings on daily life of citizens are organised, information is diffused through the website, a welcome book has been published, information panels are posted in the streets, a monthly city agenda is issued, the City Information letter is sent out to citizens.

- Methodological facilitation of the participatory process, whereby each meeting is facilitated by a facilitator – a citizen trained by other citizens, with the techniques of popular education. Each meeting is planned in advance through a guiding document with objectives, tools and time needed, the meetings are a mix of work in sub-groups and in plenary, with an equal say from elected representatives and citizens. Each session is evaluated by the participants.

[/tx_column]

[tx_column size=”1/3″]

3. Monitoring of the participatory process, through the Council of the Wise people.

Composed of 12 people, the Council monitors the implementation of the participatory democracy, supports this implementation with logistics and methodology and being responsible for recruiting and training facilitators. It also relays experience of Saillans to other interested parties.

[/tx_column]

[/tx_row] On 11 August 2016, I had the occasion to meet with two people from the Council of the Wise people: Gwenola Breton and Emmanuel Cappelin. While going beyond the now constantly discussed issues of representativeness and (lack of?) success of participatory processes, our discussion focused on the way city administrations, which are far away from the citizens’ leadership of Saillans, can learn from the city’s experience. Here are some captures of this discussion.

How has the city administration’s staff evolved since the previous legislature in Saillans?

The city council’s staff is composed of less than 10 people if we include the Secretary, three people for general enquiries, three people for works and infrastructure, the rural office, a rural policeman and childminders. The main change in the city has therefore been the elected representatives, composed of 18 people. These are the ones working directly with the administrative staff. In terms of transition, the Secretary changed with the new legislature, which did not help for the continuity of the working files.

In terms of workload, what has really made a difference is the fact that we now work with constant discussions and exchange, and especially with the fact that elected representatives work in pair to take decisions, whereas before, each deputy mayor was working in an isolated way. As such, it has become more transversal. Yet, the process takes more time as it requires additional back and forth processes. For the Secretary, it also means getting two approvals instead of one. As such, she had to adapt the way she was coordinating this work.

In addition, we know where we are going (more or less), but it is taking longer than usual to get there. This is indeed the whole process we are into: we are in a transition and do not know where we are going. This uncertainty can scare more than one person! All in all, this is about a paradigmatic change which requires a change in the mentalities of the citizens, the administration, the elected people…

To support us in our transition, we are actually getting a new position funded in September thanks to the Fondation de France: one person will be in charge of the participation in the city. We look forward for this extra resource and the learning we can take out of it.

Did you set up a (-n integrated) strategy in order to steer your governance?

The elected team has focused its approach on the process itself, the methodology, not on given targets. Indeed, the objectives are yet to be defined, step by step through participation of the citizens. Our programme is defined in the Charter we designed during the election campaign. It focused on the modalities of the governance though dialogue and transparency with a series of instances such as the Commissions and the Action-Projects groups. It also states a number of “values” which brought the different elected officials of the municipality together. This is really the Charter which has designed the structure of our current governance model.

In our approach, nothing is to be seen as fixed, not even the processes. We are learning through experimenting ways of being “direct” in democracy. It is taking more time than traditional governance model. Everybody is learning about the municipal functioning, elected representatives as well as citizens. This is really an experimentation and as such we do not have a strategy that includes the objectives nor thematic nor methodological.

What pieces of advice would you have for cities which would like to change to way they are governed, to go towards more openness, experimentation and participation?

In the case of Saillans, the whole process was bottom-up where citizens grouped together against a project of opening of a new supermarket without prior consultation of inhabitant (in a nutshell, they were opposed to a “classical” way of doing things). We were not professionals and were looking for openness and for learning about city governance. This actually questioned our legitimacy in the light of other cities and department and regional administrations. This was a risk to take.

Cities should start with two main approaches. On the one hand, they should be transparent and communicate. Too often, the city governance process and the way the decisions are taken remain obscure. It should be clear for citizens how it happened. At the same time, there should be interaction between elected representatives and citizens to get to know each other but also to share on difficulties and potential solutions on both sides. As such, cities should create spaces for encounters, where citizens and the municipality could meet and exchange, where they could co-create solutions for the city.

On the other hand, city governance should be more open to citizens. It should create platforms to discuss and exchange, benefit from those experiencing daily life in the city. Yet, this process goes hand in hand with an involvement both of the administration and of citizens. They should also set up Commissions to discuss issues which would have been chosen together with citizens in the light of the needs of the city.

This process takes time and energy as it is a fundamental change. Yet, it is worth it.

You can find more information on the governance model of Saillans at : http://www.mairiedesaillans26.fr/