Cities have shown how agile they can be in addressing increased needs of their local population in terms of access to (healthy) food. As the economic crisis unfolds and hits the most vulnerable first, it is important to think about what cities can do to sustain and transfer such good practices and what support they need at national and European level.

“The idea behind all initiatives is not to leave anybody behind during the Covid-19 crisis.” Josep Monras i Galindo, Mayor, Mollet de Vallès (Spain)

For many of the most vulnerable people, Covid-19 has not only meant immediate health risks and threats to their income, but a significant worsening of their access to good quality food. This has put them at increased risk of hunger and malnutrition.

At the same time, we have heard some positive impacts of the crisis on other aspects of the mainstream food system, for example with the development of healthier eating habits, more cooking at home and shorter food supply chains. Citizen solidarity has also been visible in many local areas to meet food needs of the most vulnerable.

In this article, I therefore ask: how have cities supported emerging citizen-led initiatives for food provision to those in need during the lockdown? How have they reorganised food aid systems, such as subsidised meals in canteens or charity-run food distribution schemes

And as the lockdown measures are lifted across Europe, what lessons can be learnt from the responses to the crisis for building resilient food systems and local food policies for everyone? How can such learning continue to ‘feed us’ and provide us with a roadmap for action post-Covid

New types of food aid distribution

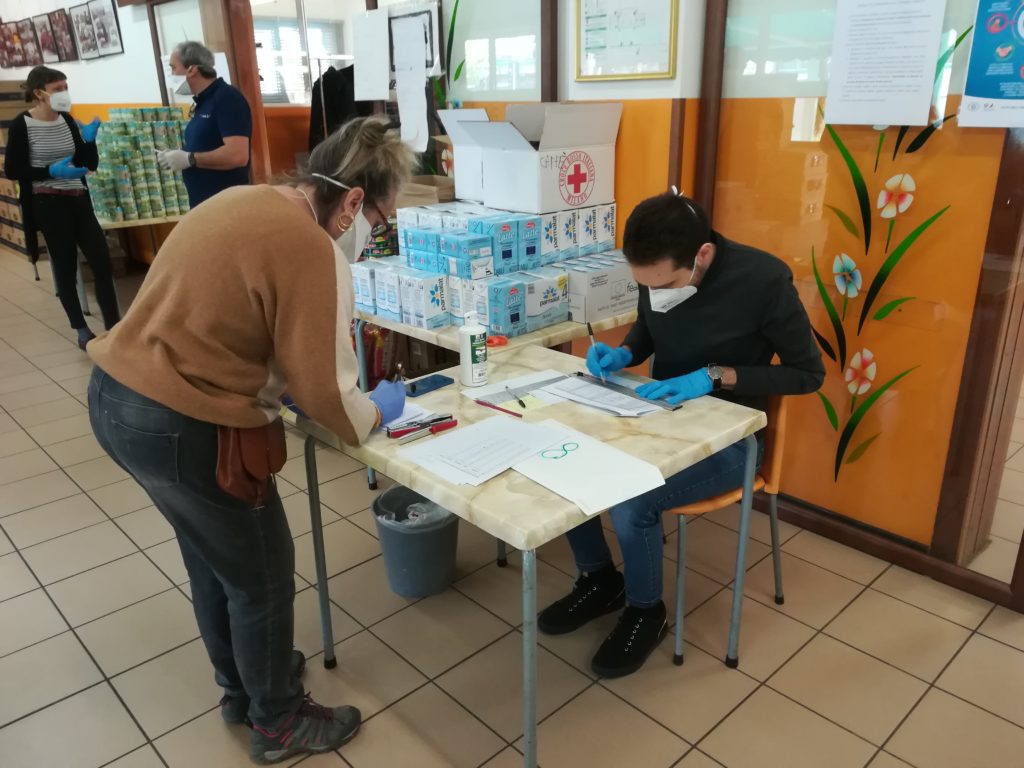

Associations and charities have faced a number of challenges during the lockdown. On the one hand, they lost the critical support of their senior volunteer workforce at risk of catching the virus. On the other hand, they faced increased demand with more people than ever in need of assistance, beyond their usual list of ‘beneficiaries’. This required significant outreach efforts. Some structures readjusted their model by recruiting new volunteers, adapting to new health and safety measures, or even changing their food provision and distribution patterns, whilst others simply had to temporarily close down.

In some cases, the government assumed more responsibilities for distributing food aid, often leading to positive effects – for example, more cross-departmental cooperation and social innovation within city administration, more promotion of short food supply chains and organic food.

The Italian large city of Milan (1.3 million), which is an URBACT Good Practice for its Food Policy, set up a new food distribution system (“Dispositivo aiuto alimentare”) to offset the impact of the closures of several associations and charities and therefore centralised the entire supply chain until the end of the crisis. Food hubs were created at 10 locations across the city to prepare food aid packages for vulnerable families and fragile persons identified as being in need by Milan’s Social Services and non-profit operators.

Around 180 people and many stakeholders have been involved, including retailers, volunteers, municipality employees, drivers and others active in the food donation system. Capacity has increased rapidly from 1,000 beneficiaries in the first week to 15,000 by the third, and the service reached in the end 20.300 people in 15 weeks. The Municipality opened within the Municipal grocery market – Foody a specific food hub where fresh fruits and vegetables were collected and distributed to the food hubs and ultimately added to the food aid packages. Therefore, this action has not only improved access, but also quality of the food aid.

Municipalities supporting citizen-led initiatives

Whilst the senior volunteer workforce has been impacted, many other groups have found themselves with more time on their hands and more reasons to engage in mutual aid. The result has been that many URBACT cities have seen a surge of volunteerism during Covid-19.

The small town of Athienou in Cyprus (6,500 inhabitants) has a long history of supporting volunteering. Recognised as an URBACT good practice, Athienou is now leading the URBACT network Volunteering Cities. As Kyriacos Kareklas, Mayor of Athienou, likes saying: “The spirit of help and volunteerism is something that gives extra power to people in charge, who want to help people in need.” The Municipality quickly reacted to the crisis by calling upon volunteers to help the elderly and people with disabilities with their grocery shopping. They also supported the engagement of various actors in the food supply chain through the Social Welfare Program and Volunteering Council.

The urgency and logistical challenges of providing access to food led in many cases to federated efforts at the neighbourdhood level. For some cities, this represented a unique opportunity to strengthen territorial cooperation. Authorities played a crucial role as facilitators – for example, by making connections, setting up platforms, making spaces and resources available, or helping with communication.

This was the case, for example, in the bigger and more densely populated city of Naples, the Lead Partner of the CivicEstate Network, which is exploring new forms of collective governance of shared urban spaces (unused building, parks, squares etc.) through an ‘urban common’ approach. This approach helped a wide network of associations, cooperatives, soup kitchens, community centres and other urban commons in Naples to rapidly organise food solidarity

As Gregorio Turolla wrote in this article: “The extraordinary situation faced by cities like Naples during the pandemic has highlighted the essential role of self-managed or co-managed spaces of aggregation and mutualism. This confirms the important role of urban commons as social infrastructures, producing public services of social impact through solidarity, creative, collaborative, digital and circular economy initiatives”.

Meeting the needs of vulnerable children

Lola Gallego, manager of health and social services at Mollet de Vallès, stressed that “the health issue is a priority, but now the social crisis is beginning, and the basic social services provided by the municipalities must be the cornerstone of the forthcoming policies, plans and actions. To provide money it is not enough. What is crucial is to accompany people in need.”

As one important example of this potential social crisis, a major risk factor for many vulnerable children, up to 320 million children worldwide, has been the disappearance of their only daily meal from school.

As part of a wider regional programme between the Catalan Government and La Caixa Bank, the Spanish medium-size city of Mollet de Vallès (52,000), partner of the URBACT Agri-Urban network, has contributed to a scheme providing credit cards for each child eligible for publicly funded school lunches (1,087 cards in Mollet). This scheme is supported jointly by the government and the city. Families were asked only to use the cards to buy food in the city where they live.

Food policies and food sovereignty for al

Andrea Magarini, Milan Food Policy Coordinator, is adamant that having “an effective local food policy has helped overcoming situations of crisis like the one we all are facing since the end of February”. In the case of Milan, their existing work “on issues such as food waste and school canteens has helped in the identification of successful actions to ensure access to food for many vulnerable groups during the lockdown,” points out Andrea Magarini.

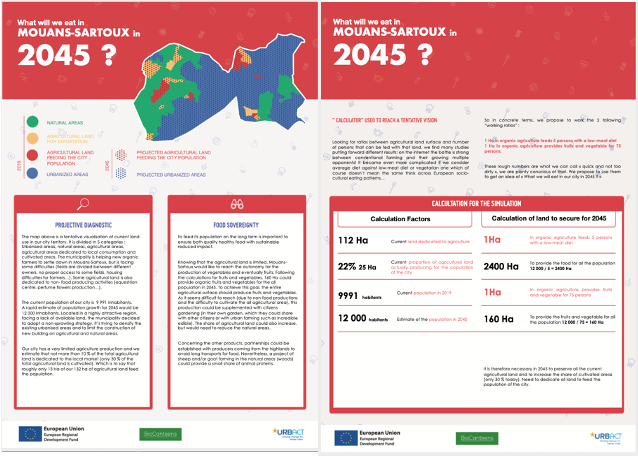

In the small French city of Mouans-Sartoux (10,000), partner of Agri-Urban and Lead Partner of the BioCanteens network, their URBACT-awarded ‘good practice’ is rooted into a territorial eco-system with strong food sovereignty. In that context, the crisis has only further entrenched their long-lasting efforts to guarantee food sovereignty on their territory.

Mouans-Sartoux plans to continue the activities initiated during the lockdown, such as the a newly set-up NGO helping homeless people. They will also launch new initiatives to support self-production and redistribution to those most in needs, education on sustainable food for everyone, improvement of the quality of the food being delivered at home, and strengthening citizen participation in the food policy.

The ‘food lever’ – how to scale up action from the bottom up?

So, what cities can do to sustain such good practices and what support do they need at national and European level?

As Gilles Pérole, Vice Mayor for education in Mouans-Sartoux said, “it is at local level that we need to act now. State centralism does not provide us with the quick and efficient answers we need. Within these first two months of crisis, the administrative burden has disappeared as we had to quickly react and adjust ourselves. The Covid-19 crisis has showed us what could happen as a result of the climate crisis and there won’t be any vaccines to save us from it…”

As part of the Farm to fork strategy which was published in the midst of the crisis, the European Commission is focusing, amongst others, on “Making sure Europeans get healthy, affordable and sustainable food”. Yet, it puts little emphasis on the role of cities except in the conclusion stating that “the transition to sustainable food systems (also) requires a collective approach involving public authorities at all levels of governance (including cities, rural and coastal communities), private-sector actors across the food value chain, non-governmental organisations, social partners, academics and citizens”.

As such, URBACT (and its partners) have a strong role to play in providing grounded evidences and cases from cities, offering additional and counterbalanced views to that of mainstream lobbies, further continuing to facilitate exchange of learning and accelerating change towards more food solidarity at local, national and European level.

Reposted from the URBACT website.