Each year, EU households throw away millions of tonnes of food. What can cities do to support the fight against food waste?

Approximately 20% of all food produced in the EU is wasted, leading to annual emissions of 186 million CO2, writes Antonio Zafra, Lead Expert of the URBACT FOOD CORRIDORS network, in a recent article, drawing on figures from the European Environment Agency. So, with more than 50% of that food waste coming from households– on average, 47 million tonnes a year – what actions can local authorities take to help us limit and prevent this waste? And how is URBACT supporting them? URBACT Programme Expert Marcelline Bonneau investigates…

Globally, the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) estimates that a third of all food produced for human consumption each year is lost or wasted. This corresponds to 1.3 billion tonnes of food wasted every year in the world, worth a total of 750 billion dollars – equivalent to the GDP of Switzerland. At the European level, this accounts for 89 million tonnes of food annually, corresponding to approximately 179 kg per capita per year (throughout the whole supply chain).

Although getting precise data is extremely difficult, we do have some figures. In the Region of Brussels-Capital (BE), for example, it is estimated that households waste an average of 15 kg of food per person per year, the equivalent of three meals a day for 30 000 people over the course of one year.

Why do we waste so much at home?

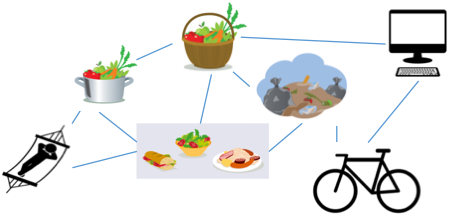

The reasons for wasting food are strongly connected with all daily activities: shopping, cooking, eating, sorting out waste, but also working, having hobbies and leisure activities, or moving around in the city, as presented in the image below:

These can also be explained as follows:

- We are dependent upon production and consumption systems:

- Available information (e.g. expiration dates, promotions…);

- Food culture (e.g. providing large quantities of food to guests, understanding of food safety and aesthetics, “cheap” food…);

- Available products (e.g. types of products, packaging…);

- Daily habits:

- Personal meaning (e.g. culinary traditions, not eating the same thing twice);

- Knowledge and competences (e.g. being able to cook, improvise, knowing the content of the fridge and cupboards, anticipating…);

- Appliances (e.g. for storage, transformation…);

- Personal influences:

- Capacities (e.g. professional framework, frequency of shopping…);

- Life experiences (e.g. available time, family, tiredness…);

- Values (e.g. enjoying eating outside, feeling guilty…).

Six tips for cities fighting food waste

Against this background, certain URBACT cities have sought to carry out a range of activities and initiatives to support households in reducing their food waste. Drawing on their experience, here are six solutions to inspire any town or city to do the same:

1. Know the food waste facts

First and foremost, it is vital to measure food waste in households in order to design adequate policy actions and instruments (see solution 2, below). But it can be extremely difficult to design adequate methodologies to ensure household food waste is monitored regularly, to collect comparable data, etc. Yet, some URBACT cities have managed to develop useful frameworks. Bristol, UK partner in the URBACT network Sustainable Food in Urban Communities, developed an approach based on food-waste hierarchy principles, underpinned by Bristol City Council’s ‘Towards a zero waste Bristol’ strategy in 2016, leading to measurable successes in food-waste reduction.

Ghent (BE) also conducted a food-waste benchmarking study to track goals, and all waste diverted through the Foodsavers Ghent programme, as well as calculating GHG emissions averted. As a member of the Milan Urban Food Policy Pact (MUFPP), Ghent is also seeking to incorporate the MUFPP Monitoring framework into its assessment strategy in order to ensure greater accuracy in measuring the impacts of its food policies. Another Belgian city, Bruges, member of Eurocities, also used a self-declaration survey for citizens to measure the impact of recipes and tips shared by the city for reducing food waste at the household level. And, still relevant eight years after its launch at national level, another very interesting study was carried out in France by ADEME (the French Environment and Energy Management Agency) to have households measure their own food waste.

2. Design an enabling food-policy framework

As we saw above and in the article by Antonio Zafra, Lead Expert of URBACT FOOD CORRIDORS network, food waste covers a range of topics. To ensure that it is addressed in a holistic way, some cities have designed dedicated policies, not only on sustainable food, but also, more specifically on food waste. This is the case of Milan (IT), labelled URBACT Good Practice for its Food Policy, coordinator of the Milan Urban Food Policy Pact and Lead Partner of the URBACT NextAgri network. Indeed, as part of its Rethinking Milan’s approach to food waste framework, the main goal is to achieve a 50% reduction in food waste by 2030. Five main focus areas have been identified:

- Inform and educate citizens and local stakeholders on reducing food losses and waste;

- Recover and redistribute food waste;

- Create local partnerships, such as among charities food banks, supermarkets and municipal

agencies; - Improve and reduce food packaging;

- Strive for a circular economy in food system management.

Related actions and initial measurements have already been made by the city of Milan. For example, a campaign encouraging the separation of organic from non-organic waste also achieved a source separation of 56% in three years, up from 36% in 2012. A first step to raising awareness about the quantity of food wasted in households.

3. Raise awareness and provide concrete tips

Before citizens can actually start reducing their food waste, they need to consider it as an issue. As such, regions such as Wallonia (BE) with “Moins de déchets” and countries such as France with “Ça suffit le gâchis”, Germany with “Too good for the bin”, and the UK with “Love Food, Hate Waste” have developed dedicated information campaigns presenting the key issues at stake. More importantly, they also share concrete tips for daily life, and activities.

In particular, since 2007, the aim of the ‘Love Food, Hate Waste’ campaign in the UK, implemented by the non-profit organisation WRAP, has been to reach out to consumers and cooperate extensively with companies, including supermarkets. They run poster campaigns, radio and newspaper announcements as well as bus-back adverts, using social media, cooking workshops and London-wide events. The ‘Love Food, Hate Waste’ website also provides tips and tools for proper storage, left-over recipes, understanding expiry dates, and measuring food-waste amounts, as well as promoting the benefits of home composting.

A ‘Money-Saving App’ also includes a portion and meal planner along with many recipes, and allows customers to keep track of the items they already bought and those they plan to buy. Avoidable food waste was reduced by an estimated 14% thanks to the campaign, with some households that actively focused on food-waste prevention reducing their avoidable food waste by 43%. Importantly, resources from these campaigns are designed for one-way communication and require minimal staff time to implement.

4. Challenge citizens

Cities should provide dedicated tools to support households with their daily fight against food waste, as well as support intermediary organisations such as NGOs or schools. For example, in Alameda County, California, the ‘Stop Waste’ public agency designed signage, including an ‘Eat This First’ sign for the fridge to encourage households and businesses to designate a fridge area for foods that need to be eaten soon.

Engaging households in activities directly has been key to ensure they are empowered to reduce their own food waste. As part of its ‘Good Food Strategy’, a direct outcome of the URBACT Sustainable Food in Urban Communities network that it led, the Region of Brussels-Capital supported the design of ‘FoodWasteWatchers‘. This is an individual and targeted programme for households to identify what, how much they waste and why, as well as to design their own strategy in order to reduce it.

Also, in 2019, the city of Oslo (NO) organised a challenge and training programme to help families halve food waste. During this four-week project, 30 families weighed their food waste, participating in a short workshop, with tools (e.g. kitchen diary and labelling) and information on how to reduce their food waste. The ‘winning’ family cut its food waste by 95%!

5. Train citizens as relays

Who is better placed to talk to citizens and households than citizens themselves? Following the success of its experience on the topics of gardening and composting, the Region of Brussels-Capital supported the training and set-up of a network of ‘Fridge Masters’: over the course of nine modules, citizens exchanged experiences and were trained on various tips and tricks to reduce food waste, from improved organisation, cooking habits, and food preservation methods to shopping in different types of shops. They were also trained in facilitating events for the general public – which they did successfully with a series of tools they designed themselves. These included social media challenges and interaction, tasters on the site, and images representing ‘fake fridges’.

6. Support solidarity

Last but not least, combating food waste by sharing what would otherwise be thrown away can be a way of connecting with other people, creating new relationships and opportunities, as well as providing food to those in need. Solidarity fridges are an implementation of such a concept.

One example is the ‘Food Share Cabinet’ in Estonia’s second largest city Tartu. As a way to raise awareness, make food available for people who need it, and redistribute what would have been wasted, a temporary ‘food share’ cabinet was installed on Tartu’s ‘Car Freedom Avenue’ event as a Small Scale Action, with the support of the URBACT Zero Carbon Cities network. Shelves and a refrigerator enabled caterers from the event and neighbouring cafes to share their leftovers. This action is now part of the Tartu City Government reflexion with the food-share community to reduce food waste in the city, working with local food businesses.

What will your city do next to reduce food waste?

This listicle has shown a range of frameworks, instruments and activities used by cities to reduce food waste in households. But this is only one part of the equation. Food waste needs to be tackled along the whole supply chain.

Check our Food Knowledge Hub page for further insights, as well as the Glasgow Food Declaration resources.

Last but not least, look out for the upcoming activities of five current Horizon 2020 projects which will test further actions:

- Food Trails: https://foodtrails.milanurbanfoodpolicypact.org

- FOODSHIFT2030: https://foodshift2030.eu

- Cities2030: https://cities2030.eu

- FUSILLI: https://fusilli-project.eu

- FoodE: https://foode.eu/

What can you do to cut waste in your town? Let us know – we’ll be curious to read about your experiences – reach out to us via Twitter, Facebook or LinkedIn!

Facts and figures

- Bruxelles environnement (2020) Le gaspillage alimentaire

- EU barometer survey (2015) Flash Eurobarometer 425: Food waste and date marking

Bonneau M. (2021) Changer les modes de gouvernance en appliquant de nouveaux cadres analytiques : le cas du gaspillage alimentaire à Bruxelles - FAO (2013) Food wastage footprint – Impacts on natural resources

- Fusion (2016) Estimates of European food waste levels

- Zafra A. (2022) A FOOD WASTE URBAN APPROACH – To reduce the depletion of natural resources, limit environmental impacts, and make the food system more circular

Reposted from the URBACT website