The UIA TAST’in FIVES project, taking place in the Fives neighbourhood of Lille, France, has aimed at using the concept of food (from growing, picking up, preparing, cooking, and eating) to propose a systemic model to fight against urban poverty, including social and economic inclusion, health, education, and empowerment. Indeed, with a population of 20,000 inhabitants, 50% below 30 and 22% unemployed, 45% of the households of Fives live below the poverty threshold[1]. More than 1,000 families receive food parcels from the Secours Populaire Français. The area suffers from poverty, with under and malnutrition, as well related health issues (obesity, cholesterol, diabetes….).

Yet, TAST’in FIVES has not sought to address those directly and to carry out a top-down health-focused project convening moralising tips for everyday life: it has intended to provide a convivial place and useful activities where each participant could find a direct benefit from herself or himself. While indirectly addressing poverty issues, it sought to have a wider impact on residents’ lives, using food-related activities to create commensality, share moments, empower, enable socialisation, develop skills, and support access to the job market.

A realm of stakeholders and activities seeking to reduce urban poverty

TAST’in FIVES has been prototyped during 3 years, before the final building and activities will be launched in Spring 2020[2]. Its temporary location, l’Avant-goût, has hosted seven main types of activities:

· In an urban greenhouse: urban farming. Activities around growing, recognising and picking up vegetables;

· In a shared kitchen called “the Common Kitchen”: cooking workshops, food events, video-making, food distribution, job search and entrepreneurship.

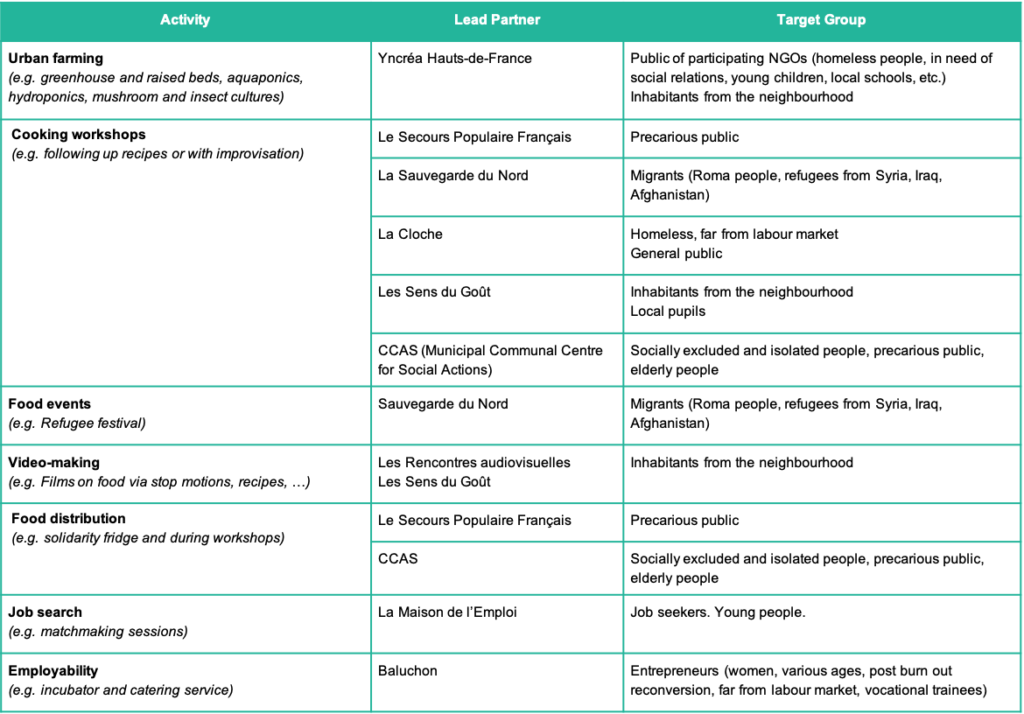

Each of them was organised by a variety of stakeholders (often jointly), who mobilised their own target groups as presented in the table below and as referred to throughout this article (this table presents the main organisers of activities bearing in mind that many other organisations have used the placed as well, to a lesser extent) .

Evaluating the impact of the activities on the reduction of urban poverty is a difficult task. For example, officially, the objectives of the Common Kitchen were to “facilitate the relations between the inhabitants, and between the population and the social services; making the kitchen a collective tool to break the isolation of a population in precariousness situations; fighting against prejudices and stereotypes; and mixing the local community with the best of food-professionals and economic stakeholders”[3]. The use of indicators will enable addressing some of the effects of this work in qualitative and quantitative terms, yet, without a total certainty of direct impact in this uncontrolled environment. In addition, declaring that such a project had a striking impact on local urban poverty in such a short period of time, with a perfectly designed methodology, would be presumptuous. Beyond a mere patronising account of the impacts of the project, we will therefore here seek to sketch some influence the food-related activities seem to have had on its beneficiaries and its organisers in reducing urban poverty.

Food activities as gathering and benefiting those in need

The activities we focus on here took place in the temporary location of l’Avant-goût (a 1800 m² brownfield outdoor area with a temporary bungalow hosting the Common Kitchen, and an “urban greenhouse” made of a container, a greenhouse, and raised beds). L’Avant-goût was indeed designed as a physical space for gathering residents and NGOs for collective use, where residents would be welcome to come and join activities for free. As part of the wider urban regeneration project, they were also invited to become actors of their neighbourhood and of the future design of the project. Some residents for example took part in co-creation workshops on the future building.

As a physical space, l’Avant-goût has therefore distilled some elements for a new everyday life of activities’ participants: they have been given the opportunity to attend workshops to meet and exchange with others, without any commitment, regularly if they wished, with the option to remain in contact outside this frame, but with no obligation. This parenthesis has been for many the opportunity to move away from their daily issues, and daily environment: for some mothers especially, the activities have provided them with a space other than their home. As such, La Sauvegarde du Nord has organised (cooking and video) activities during school time for them to be able to come and attend.

For some, it has also enabled them to focus on an activity they like or find interesting. For example, the Secours Populaire Français has observed that those coming to the workshop classes were interested by food and wanted to “be in contact with others”. It has alsoenabledactivating their pleasure of cooking (as an activity), cooking for oneself or for others, as well as, eating (as a basic need) or eating nicely cooked dishes. In turn, these have led to improve self-esteem. Valorisation also became quite apparent during the job search activities organised by La Maison de l’Emploi where applicants were observed during some cooking activities to showcase their skills to potential employers and recruitment agencies.

For others, food has been an excuse to meet and socialise. As some participants acknowledged, “it is not necessarily about learning but being together”. In the case of La Cloche, the invitation has been for all those interested (homeless people but also the “general public”) to gather and cook on the basis of what was available. Within the activities of the Secours Populaire Français, those who are helped will often help in return. Discussions have sometimes also led to identifying solutions to everyday life issues (such as administrative, getting access to food, etc). La Sauvegarde du Nord has also witnessed the empowerment and openness to the city as its beneficiaries became independent in their mobility, while eventually all going to the activities in public transport (often combining a few for up to 1 hour) by themselves. Such gained mobility will be beneficial for all their other private, social or work-related activities.

The activities have been free and open to all those interested, potentially creating a space for cultural encounters, people to come and take part in a collective project. For example, La Sauvegarde du Nord has noted that their beneficiaries (migrants) had got to know each other’s cultures in this location outside of the kitchens many share on a daily basis with other families – with whom daily housekeeping and usage provoke tensions. Their relation have become positive with a real possibility and wish to familiarise with others and their cultures. CCAS is also working with the “senior space” of Fives and retirement homes to organise intergenerational activities.

The activities have also provided a frame for those who wish to have one for their daily lives. The cooking activities, for example organised by La Sauvegarde du Nord, La Cloche, Les Sens du Goût and Le Secours Populaire Français, also giving the room to the participants to propose their own recipes and ways of cooking. Participants have got empowered and stimulated further cultural and personal exchange, at the same time as being proud of their own learnings. The seeds bank created by Yncréa Hauts-de-France and managed in a participatory way has also served both as an end and as a mean for personal investment and learning from the overall project. Yncréa Hauts-de-France has also invited the beneficiaries of the partner organisations to help managing the chicken coop, producing endives or mushrooms, feeding insects of fishes, sowing, or adjusting fertilizers. Aquaponics, hydroponics and raised beds harvests have directly targeted the cooking workshops to keep a link between the seed to the fork. This way, the cooking classes have also been a way of supporting French learning or communicating in a group, as La Sauvegarde du Nord analysed.

The activities with children have also enabled reaching out to more families. La Sauvegarde du Nord has seen an increasing interest of (small) children gaining confidence in being integrated in the food activities along the months. Whether it was picking up vegetables from the greenhouse or raised beds (managed by Yncréa Hauts-de-France) or cooking, they could put their hand in the work and do for themselves.

The variety of activities organised has furthermore provided for a basic need which isfood: for example, the cooking classes and food events provided food for free for those in need. The solidary fridge, coordinated by CCAS, sees a constant flow of givers and receivers, demonstrating local solidarity as well as need for it. In addition, a partnership with the Local Short Food Supplier, proposes “suspended vegetables” which are made available in the fridge.

The catering sector faces difficulties in recruiting adequate employees. As such, some job matchmaking organised by La Maison de l’Emploi have benefited from cooking activities to assess the overall competences of job applicants and support them and job providers to find the most suitable job opportunities in the food sector. The incubator led by Baluchon offers coaching meetings and thematic training sessions for those wishing to set up a food. The beneficiaries of some activities, e.g. organised by Les Sens du Goût or CCAS (Centre for housing and social reinsertion), were also redirected to the incubator to create their professional activity in the food sector. La Cloche in addition works on the volunteer’s acquired skills and independence: they would for example strengthen the posture of volunteers becoming workshop facilitators themselves and for intend to acquire a cargo-bike in order to give them full autonomy. The upcoming catering service – also led by Baluchon and currently under feasibility study – will also provide directly employable skills and job opportunities for unemployed people. Some organisations have also noted some indirect impact on job creation where for example one person who was beneficiary, from La Cloche became a volunteer then found a job and housing.

For those in need of it, health issues have been addressed indirectly by the mere fact of cooking (instead of buying processed food) and some general tips about “lighter food”, for example, in the case of cooking workshops organised by Les Sens du Goût. It has also been the case by going back to the roots of food, i.e. food production, with the above-mentioned seeds bank created by Yncréa Hauts-de-France: together with La Cloche, this box has been opened to any person wishing to grow reproducible regional fruit and vegetables promoting non-market economy. Some seedlings were exchanged permitting to share knowledge on food production.

Finally, food entry was also a way of considering family budgeting while finding the right balance between healthy and cheap products, reducing food waste, making the most out of existing products, as was for example shared during the activities organised by Les Sens du Goût.

Food activities as an opportunity for new ways of accompanying those in needs

As La Sauvegarde du Nord noted, for precarious populations coming from other countries, the only way to survive with limited money is to cook. For “local” populations, getting access to cheap -and often ready-to-eat- food might be the priority without the necessary knowledge nor time for cooking, as well as getting access to what consumption society has to offer[4]. Yet, food is a basic human need: we all have to eat. This is an activity that is shared by all. As shown above, food can be used in order to mobilise people as an entry point to create conviviality and trust with the organisation.

For the partners of the project, the use of food has enabled testing out new ways of working. Some were already carrying small-scale cooking (and baking) activities such as La Cloche. Yet, La Cloche did not have a space for upscaling these activities in Lille – although there was a strong interest and grounded skills amongst volunteers for such activities – and was happy to benefit from L’Avant-goût’s Common Kitchen. It has used the space to provide an enabling framework, letting its beneficiaries to meet and exchange in an organic way. Others, such as the Secours Populaire Français, have developed activities they had never developed before. It was also new for them to have an adequate place for such activities. For this, they have relied heavily on the motivation and involvement of one volunteer, who became an important driving force: to invite, organise, and facilitate the cooking workshops.

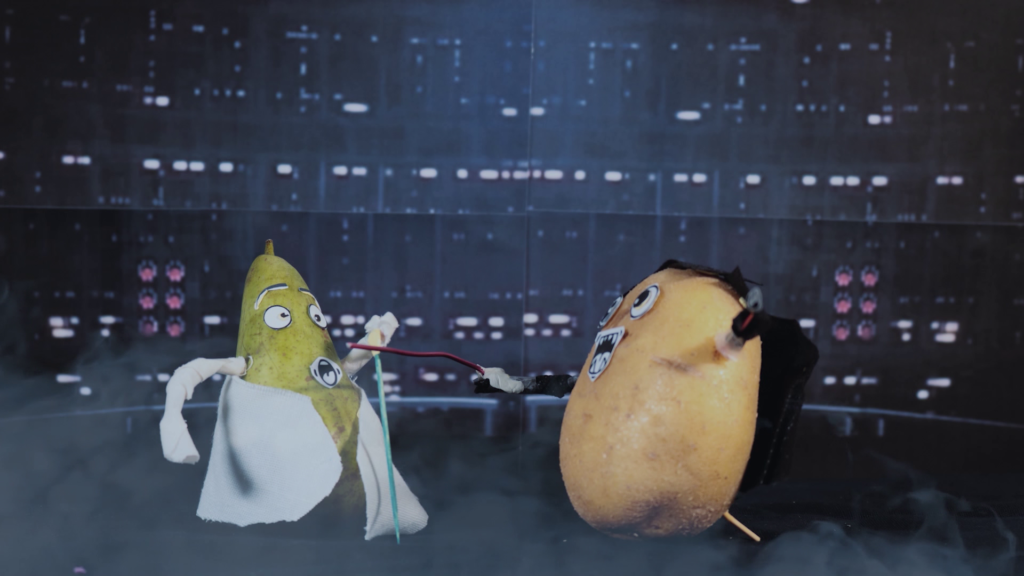

Food activities have also been used with other tools which can support the development of a realm of skills and attitudes, such as photo, cinema or culture. Les Sens du gout for example have made videos of recipes presented by the local residents. In the case of the job-search related cooking activities organised by La Maison de l’Emploi, it was not only the participant’s cooking skills which were tested but their overall their transversal skills (e.g. organisation, teamwork, etc.).

La Sauvegarde du Nord also noted that, as compared to its other activities, the space provided here was more neutral and informal, enabling it to reinforce supporting and educative measures in a new territory.

Some of the organisations had to learn new methodologies for interacting with their beneficiaries, for example La Sauvegarde du Nord who had never organised cooking workshops before and was stressed each time as to whether they had done the right shopping. It has also enabled them to look at their beneficiaries in a new light as those participants who appear to feel confident and “at home” in a kitchen, a positive approach as opposed to the focus on their issues, which are dealt with when the NGO meets them for their regular support. They have in turn invited their colleagues to witness this way of working inviting them to become inspired. For the CCAS as well, workers have got the opportunity to work outside the strict institutional framework, to promote proximity link at the same time as putting themselves at the same level as their beneficiaries: by cooking and talking about food, they would become reduce barriers preventing one and the other to get to know each other and trust each other.

Some organisations have also worked with intermediaries to further expand their experience, such as parents at schools as well as training teachers and school nurses in the case of Les Sens du Goût. CCAS is working with professional of care sector to support the quality of food provided to elderly.

The Common Kitchen has also enabled to create new synergies supporting in the joint attraction of each other’s publics, of new public (e.g. those affected by social invisibility) and new methodologies. For example, “workshops and videos” were organised jointly by La Sauvegarde du Nord, the Secours Populaire et les Rencontres Audiovisuelles. La Cloche is also currently seeking a collaboration with Pole Emploi as well as with some companies and catering services. Baluchon is also seeking the same types of collaboration for its inclusive incubator and insertion catering service. Yncrea Hauts-de-France has collaborated with the other partners to showcase different low- or high-tech microsystems that could be developed at home, in class, in associative or public structures in a collaborative way.

This mutualised tool has given stakeholders the opportunity to share and exchange on common issues, with different publics, focusing on fighting against exclusion, public health, cooking for children, job development. Such platforms already existed in Lille but they were generalist. The effect of such synergies was also observed in some participants taking part in some (or all!) the activities of each of the organisations. CCAS has for example increased (paper) communication with local shops and inhabitants via the distribution of flyers by Civic service students”.

The workshops and activities, e.g. “Apéro Sans Frontières” (“Aperitif without borders”) have enabled several shelters, emergency accommodations and “Maisons-relais” to join increase collaboration with La Sauvegarde du Nord, as well as to ask for support in organising to carry out similar activities. During the European Heritage Days and the International Solidarity Festival, CCAS is also bringing together other organization to exchange on the specificity of Food in Africa.

Looking at the Future

The main success of the activities can be explained by the skills and involvement of all the partners with their varied profiles, beneficiaries and activities. Synergies, reflexions and experimentations in order to leverage on urban poverty have been nested for 3 years by all the stakeholders via all the above-mentioned activities in L’Avant-goût. It could have also been linked to the type of space provided: informal, seemingly made out of odds and ends, where participants and organisers could get a feeling of lack of control, “not too neat”. The new location will be recently built, following strict sanitary rules and regulations, potentially giving it a “colder” feeling. It will be important to prevent the disappearance of this feeling of freedom.

Using food-related activities to seek and leverage urban poverty within the TAST’in FIVES project has shown effects both on individuals as well as on the involved organisations. The way it will affect the neighbourhood as a whole will be seen in the next few years. These will probably be acupuncture points in the local life[5], addressing some issues – like poverty – via an alternative entry point – food- , as it has proven to be successful – or while supporting other activities. There will be room for experimenting with increasing mix and synergies between activities and publics on the site of Chaud Bouillon!, the resulting building of the project. Also, the future location will enable going one step further for employability (with a functional professional kitchen) both through the incubator and the catering training. Once the experimentation phase and ad hoc funding will be over, partners will for sure be eager to keep on collaborating and carrying out their activities in the Common Kitchen, the Professional Kitchen, and the Food Court. Hopefully the learnings from these three years will continue being used and leading to new opportunities.

[1] For more background, see also Houk M (2017) TAST’in FIVES Project Journal N°1

[2] See article “Testing a future Food Court by prototyping it in real-life: lessons from the experience of UIA TAST’in FIVES’ L’Avant-goût”. With regard to the covid-19 crisis, the launch of the building and activities has been delayed until Spring 2021.

[3] TAST’in FIVES application form

[4]MASULLOA., Régnier F., Obésité, goûts et consommation. Intégration des normes d’alimentation et appartenance sociale, Revue française de sociologie 2009/4 vol 50.

[5] Jégou, F., (2010) Social innovations and regional acupuncture towards sustainability, in Zhuangshi, Beijing

Reposted from the UIA website.